How it ended - Take 1

I’m sharing how things ended with me at Microsoft, and it didn’t end great. If it was good it wouldn’t have ended; at least not quite yet.

I have a love/hate relashionship with work. In my early years, the amount of work and the weight of the work was crushing and I’d just want it to stop. I did stop once in 2005 when I moved to Beijing and again in 2010 when I left Microsoft for the first time.

This time was a little differant in that I was no longer a good fit and I wasn’t wanted. But I get ahead of myself.

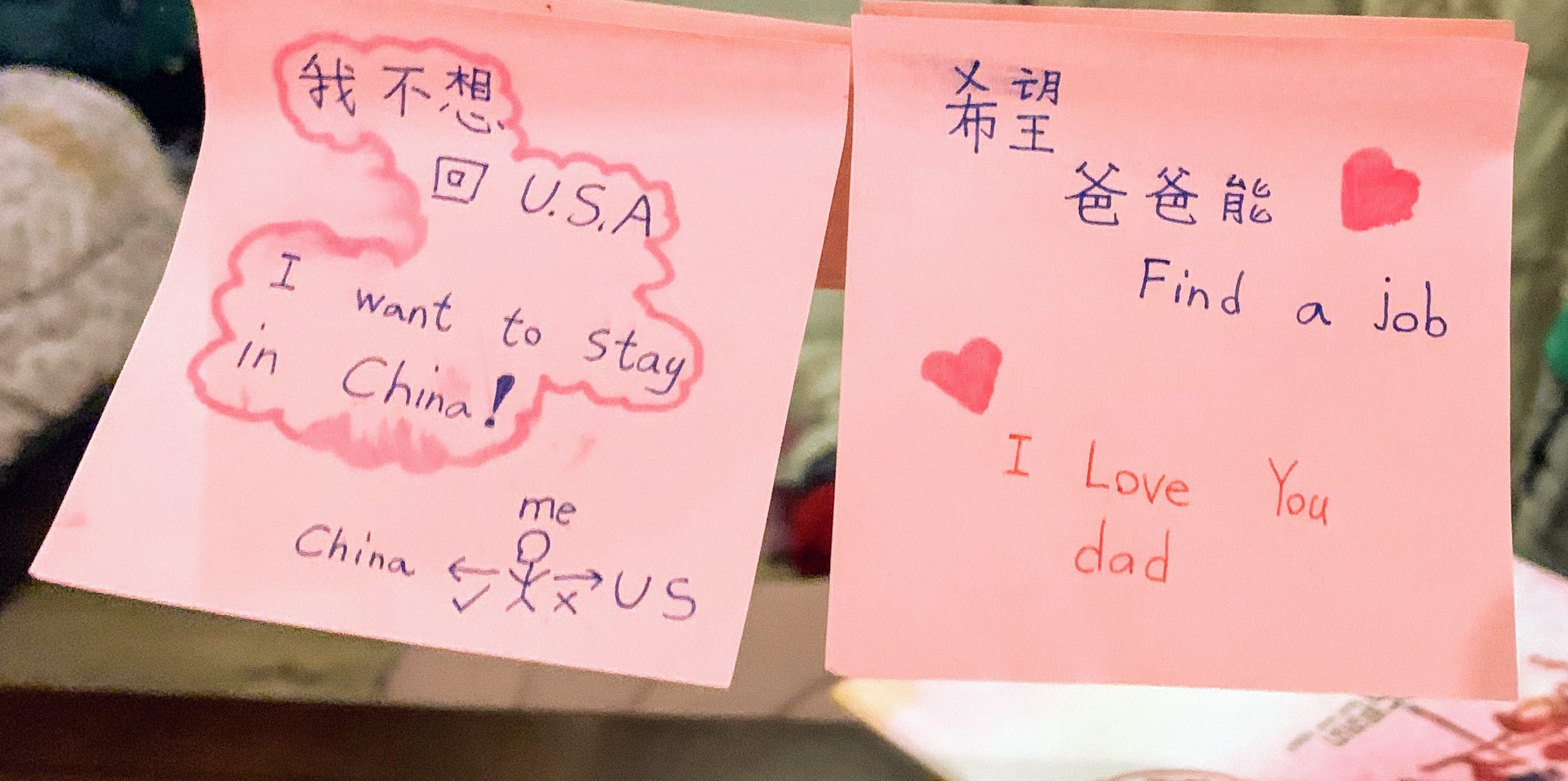

In the early months of 2019, I found out that our PowerPoint Online team in Beijing was going away. That meant the 60 of us who worked on it had to either find a new job or be laid off. It left me at a crossroad professionally. Was it time to step away? Was it time to move back to the US as disruptive as that would be to me and my family? My then 10 year daughter Elisa left these notes in her room.

If I was to be brutally honest with myself, I had insecurities about being able to relocate to the US and/or find another job in China. I took the advice of my manager at the time, Yongdong Wang, to first save myself and then figure out the next move.

There were two relevant openings with the Bing team - the Relevance GPM and the Platform GPM. During my first stint with Bing, I had avoided Relevance PM work; it seemed like black magic to me.

With that, I accepted an offer to become the GPM of the Bing Platform team in Beijing. I accepted the offer with trepidation. When I originally left Microsoft at the end of 2010, a dev manager I had worked with asked to meet me. I thought he wanted to make nice over all the great work we did together for Bing Multimedia, News, and the CJK markets. Instead, as the new Platform dev manager, he told me he didn’t think PMs were needed anymore. Although the dev manager has since moved on, the ice pick he planted still stings.

I started the role in May of 2019 and tried to be helpful. Truth be told I struggled and was soul crushingly bored from the start. The team in China was loosely coupled with HQ with highly technical initiatives that did not depend on deep customer understanding nor my judgment. The two existing PMs on the team were well versed in what we were doing, but not why we were doing it. The “why” was expressed “Richard said so” or as a metric that needed to be moved without understanding the product impact of moving it. That’s if there was even a metric. Meanwhile, I found my peers and leadership team had an understanding of the product impact but did not question the priorities or opportunity cost. At the end of the first week, I realized to effect change this was probably a five year commitment.

My failure was not affecting this change.

In 2020, there was a shuffling of the execs in HQ including our main sponsor. Over the next six months we went from loosely coupled to very tightly coupled. This held promise for me, for one of my strengths has also been with HQ partnerships. My challenge however, was our new HQ sponsor exec was not an ally of mine. He immediately kicked me out of the LT, preferring to have the dev manager as the sole China representative. He lead not with strategy and tactics, but by doing precision QnA during all reviews and status updates. He expressed limited understanding of the PM discipline and seemingly only valued PMs when they were pushing execution. I saw him as a bully and I was not wrong. I thought that as we worked on projects together, he would see the value in what I actually did. This never came to pass.

Instead, I tried to have an impact by growing my PM team’s capabilities, establishing a PM culture in the larger org, and taking on the Relevance PM team (into the dark arts). All these activities kept me busy. I was still struggling with having a product impact. I was often out of my depth on both the ML and platform side. I should have sought out other opportunities but ego, pride, and inertia got in the way.

In retrospect, there were two turning points for me. The first was when the larger China team reorged under a single leader to mirror the HQ organization. It turns out the new leader, my skip manager, was not a fan of me. Or became not a fan. I never found out why. The second was when the HQ GPM left and his successor also left in short order and then HQ eliminated the position. This left me without an ally either in China or in HQ. Maybe more importantly, it pushed down the role of PM in both the China and HQ organizations which were already very dev driven. Without a strong PM organization, it is almost impossible to have a strong PM discipline. It’s almost impossible because discipline specific culture is not recognized, cultivated, or rewarded.

The final nail in the coffin was when my direct manager decided to join another team and was replaced with a strong technical leader who was at best as agnostic to me. He canceled vehicles I used to have impact, like ship room, product reviews, and planning meetings in favor of written documents. And while I supported him and the cultural shift he was trying to make, he did not support me. There was no coaching or feedback on the documents that I produced or projects I ran. I later learned from him that if he does not comment on a document, that means he doesn’t see any value in them. To be fair, I’m sure he’s a great IC. Lest you think, I am playing the victim card here, I am not. I am sharing my direct experiance.

Let’s get a little deeper, why did I fail.

First, at the top, I want to acknowledge I was a poor fit to be the Platform GPM.

The core of the problem was structural. Our team in China had many, many projects. Some were wholly owned components (think “box” on an architecture diagram), some were “programs” (ie, enforce a latency policy across the org), some were shared projects with the product authority in HQ. My wheelhouse as a GPM is to own a product, like I did with PowerPoint online. As a Lead PM, my wheelhouse was to own a related portfolio of a product like I did with Bing Multimedia and Office365. There was no product or related set of products here, certainly nothing tightly related. Value was not seen in upleveling the conversations, say to the engineering experience for data scientists. What the team really needed were ICs, specifically technical program manager ICs.

So from July 2022, I took on several IC projects that came out of our top down planning process. An E2E testing system, a new version of the test index, a new query processing system, a distributed database, and a few others. None of these projects ended up being successful. What they had in common is they were lower priority for the already overloaded team. And I must admit, I am not a great IC at driving cross team projects when teams are not motivated. From January 2023, my IC workload decreased and I didn’t take on new projects since (a) there were no interesting ones and (b) I was about to become a father for the fourth time. When my annual rewards were determined in June of that year, I had received a lower than expected rating. My manager told me that it was because I didn’t do IC work and that I got little/no credit for my team’s work. Going into the next year, I picked up projects after my maternity leave was over and received even lower than expected results the following review cycle. There was no performance explanation on why I received low rewards. None. I could see the writing on the wall and told my manager prior to the rewards communication that I would be taking an extended leave and likely not returning to the team.

I could get a little darker about why I failed. About a progressive lack of inclusiveness. About the lack of transparency. About being an outsider. About a lack of curiosity from leadership. About being ghosted by leadership when asking for help. But I won’t go there.