I’m sitting in a conference room in Topeka, Kansas. Next to me is Mimi. Across the table are two doctors and an intake coordinator. The younger of the two doctors is explaining the program to Mimi. She’s not pleased. The doctor is leading up to his big reveal - he’s researching a hypothesis that a childhood strep infection can lead to anorexia (link). Once the big theory is exposed, Mimi, frustrated, asks for the senior doctor to say something.

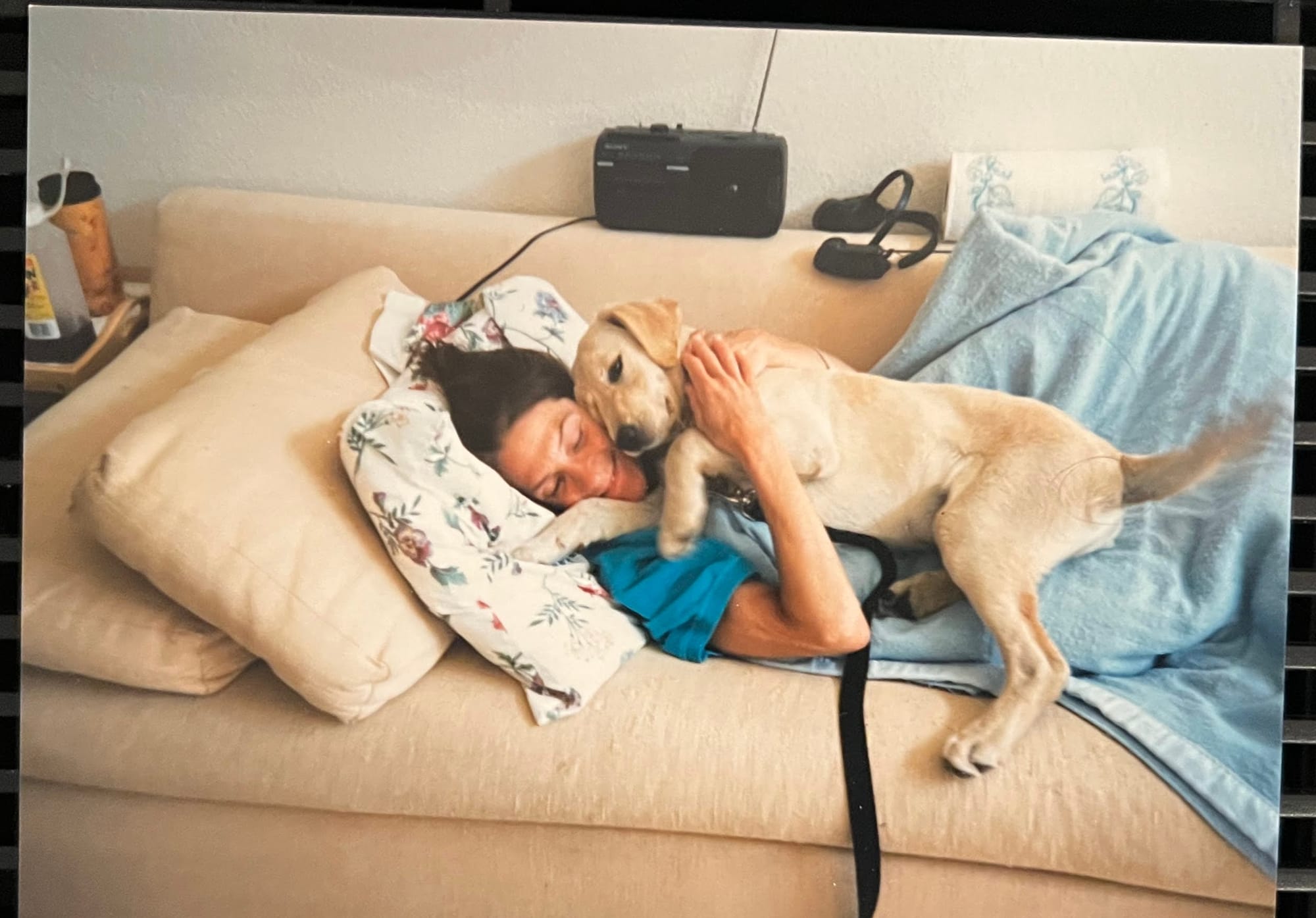

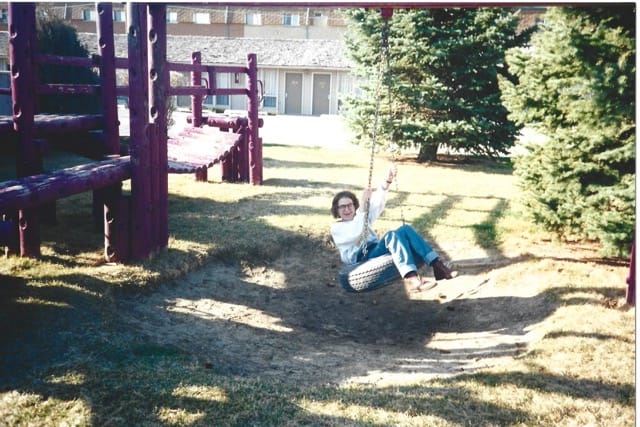

Mimi and I at Menninger clinic waiting for her to be admitted

Mimi and I at Menninger clinic waiting for her to be admitted

In a few hours, Mimi would be in a locked room and I’d be making my way out of Topeka.

How did we get here? I met Mimi when I was 23. She was 29. At a diner, on our first date, she told me she had an eating disorder. That, she was doing “ok” but she might not always be “ok”. Probably wouldn’t be. She was also five years removed from the suicide of her first husband. At first, I thought she was trying to scare me away and later learned she was just open this way. Telling her story. I think I had a burger and she had tea.

In our early days, Mimi’s struggle was like an eccentric part of her personality. A hard boiled egg on plain bread for lunch, mailing herself letters about her feelings, having a scale for food but not her weight. Things started to turn when she stopped prozac due to the high cholesterol it caused. Maybe things had already turned. As close as I was to her then, it was Mimi’s lived experience and what I saw as eccentric was closer to free soloing El Capitan.

Fast forward eight years and Mimi and I were living in a townhouse we bought. We had a labrador retriever, CJ (short for cuddle joy). Mimi loved CJ along with her heating pad. Mimi went to therapy and meetings and really worked at both. Despite her best efforts, Mimi had been in and out of the hospital several times due to malnutrition.

In my logical brain, I knew it was a disease, with no more control than someone who has cancer. I wouldn’t leave a wife with cancer, would I? I wasn’t that kind of man, was I?

But I was. I was 29 and full of life. Full of something. I wanted more than to sleep alone and listen to retching followed by toilet flushes. So, I left. I’m not sure if my leaving really triggered it, but soon after Mimi decided to enter treatment at Menninger Clinic. The plan was she would be an inpatient for a couple of months and then an outpatient for several more months. I forget the exact durations.

Back to the conference room - the senior doctor spoke. It was neutral as far as I can recall. Mimi was not satisfied and wanted to call the whole thing off and I was doing mental gymnastics on how to support such a decision. Then at the last minute, Mimi agreed to be admitted. Mimi and I were led to a ward and I was allowed to enter it with her. It was a long hallway, with rooms on either side. Mimi would have her own room but she would not be allowed to leave until she met certain milestones, like eating and digesting her meals.

As I left, I looked back to see Mimi looking at me out her window. I snapped a picture and felt a part of me that wasn’t broken.

I left our car, a Ford Ranger, in the parking lot with a key in a place she could find. I left a note for her to read when she got out. And with that, I walked down the hill and to the nearby hotel. The next day, I’d take the shuttle to the Kansas City airport and fly home.

In the weeks that followed, I kept myself busy. Full time job, grad school at night, dog runs in the morning and night. There was a time restriction on when I could call Mimi - I think the clinic only allowed a call once a week. At first, Mimi wanted out. She really wanted out. The place was too restrictive. She didn’t think she was getting the right help. I encouraged her to stay, they must know what they are doing. While I believed this, selfishly I wanted some time alone as hard as that is to admit. She found the courage to stay.

As more time passed, Mimi made progress. She could leave her room. She could go on supervised outings on campus. She could practice her art. Her mood became more positive. And when it became time for her to leave the inpatient program, she couldn’t wait for me to see the changes.

So, I flew back to help her transition to the outpatient program. I got a room in the same hotel two days before her release. I don’t remember why early, I guess it was to ease the transition for both of us. We went on a Walmart shopping expedition with other patients. It was the first time I saw OCD sufferers first hand and how they try to manage it. I saw where on campus she had art class. Mimi told me the stories of the close friends she made. I knew of the bond that can bind those in struggle.

Mimi’s transformation was tremendous. She went from looking like she was dying to healthy and fit. Her brain was sharper, her wit fully engaged. We went back to the hotel and made love. It was eye opening. It was also the last time we would be intimate in that way.

The next day, or maybe it was the same day, we checked out the room she planned to rent while being an outpatient. It was clean, safe, and close enough to campus. In a few hours, she shared second thoughts about staying. She wanted to be home.

So, the next day we got on I70 and headed west. One of the friends she made put together a mixtape. A lot of Tori Amos. We stopped for lunch in west Kansas, it might have been Colby or Goodland. We ate at a buffet, a Country Kitchen or Golden Corral. A buffet probably wasn’t the best choice. On the way in, Mimi told me expectantly, “watch how I eat now”. I watched how she made her way through the food. First with confidence, then with trepidation. By the time we got back on I70, I knew the struggle had found a beachhead.

The drive to Topeka was in some ways an adventure. A 1700 mile road trip with stops Nevada, Wyoming, and Colorado. We took photos along the way and slept next to each other in hotel rooms. There was the excitement of the unknown.

The driving home from Topeka was different. Mimi seemed to be trying to walk the endless tightrope of recovery knowing she could fall at any moment. For my part, I was starting to feel anxious. I wanted to be free from this. There was the curse of the known.

When we returned home and retrieved CJ from the kennel, I tried to make it work. For a few days. Then I called my brother Jimmy and asked if I could sleep on his coach for a while.

Mimi would relapse and return to Topeka for outpatient treatment. She bought a condo and lived in Topeka for maybe two years before returning to the bay area and the really dark times.

I write this on the day Mimi would have turned 66.